On Wednesday, September 18, 2013 Ben Bernanke gave his scheduled press conference.

From Ben Bernanke’s opening comments:

In the Committee’s assessment, the downside risks to growth have diminished, on net, over the past year, reflecting, among other factors, somewhat better economic and financial conditions in Europe and increased confidence on the part of households and firms in the staying power of the U.S. recovery. However, the tightening of financial conditions observed in recent months, if sustained, could slow the pace of improvement in the economy and the labor market. In addition, federal fiscal policy continues to be an important restraint on growth and a source of downside risk.

Apart from some fluctuations due primarily to changes in oil prices, inflation has continued to run below the Committee’s 2 percent longer-term objective. The Committee recognizes that inflation persistently below its objective could pose risks to economic performance, and we will continue to monitor inflation developments closely. However, the unwinding of some transitory factors has led to moderately higher inflation recently, as expected; and, with longer-term inflation expectations well-anchored, the Committee anticipates that inflation will gradually move back toward 2 percent.

also:

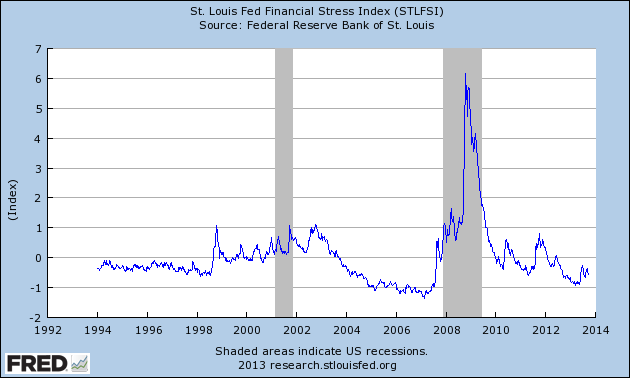

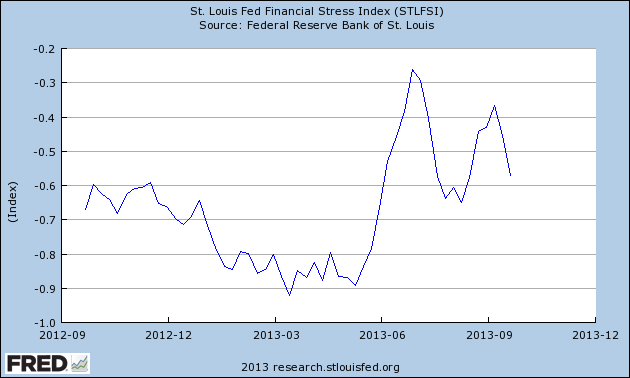

At the meeting concluded earlier today, the sense of the Committee was that the broad contours of the medium-term economic outlook—including economic growth sufficient to support ongoing gains in the labor market, and inflation moving toward its objective—were close to the views it held in June. But in evaluating whether a modest reduction in the pace of asset purchases would be appropriate at this meeting, however, the Committee concluded that the economic data do not yet provide sufficient confirmation of its baseline outlook to warrant such a reduction. Moreover, the Committee has some concern that the rapid tightening of financial conditions in recent months could have the effect of slowing growth, as I noted earlier, a concern that would be exacerbated if conditions tightened further. Finally, the extent of the effects of restrictive fiscal policies remains unclear, and upcoming fiscal debates may involve additional risks to financial markets and to the broader economy. In light of these uncertainties, the Committee decided to await more evidence that the recovery’s progress will be sustained before adjusting the pace of asset purchases.

Bernanke’s responses as indicated to the various questions:

PEDRO DA COSTA. Thanks, Mr. Chairman. Pedro da Costa from Reuters. You cite meaningful progress on the labor market both on the unemployment front and in terms of payroll growth. But much of the decline in the unemployment rate has been due as you know to the decline in participation. So my question to you is and also on the payroll front, some people would argue that, while there has been growth, it hasn't been strong enough to keep up with population growth and make up the gap that we have from the recession. So, how high do you think the jobless rate would be if it were not for the decline in participation? I've heard estimates as high as 10 to 11 percent. And could you put the labor market in that context?

CHAIRMAN BERNANKE. Certainly. So, I think there is a cyclical component to participation and in that respect, the unemployment rate understates the amount of sort of true unemployment if you will in the economy. But on the other hand, there is also a downward trend in participation in our economy which is arising from factors that have been going on for some time including an aging population, lower participation by prime-age males, fewer women in the labor force, other factors which aren't really related to this recession.

Over the last year, the unemployment rate has dropped by eight-tenths of a percentage point. The participation rate is dropped by three-tenths of a percentage point, which is pretty close to the trend. So in other words, I think it would be fair to say that most of the improvement in the unemployment rate, not all, but most of it in the last year is due to job creation rather than lower participation. I would also note that if you look at the broader measures of unemployment that the BLS publishes including part-time work, including discouraged workers and so on, you'll see that those rates have fallen about the same amount as the overall standard civilian unemployment rate. So, I think that there has been progress and it's obscure to some extent by the downward trend in participation. But I also would agree with you that the unemployment rate is, while perhaps the best single indicator of the state of labor market is not by itself a fully representative indicator.

also:

JON HILSENRATH. Jon Hilsenrath from the Wall Street Journal. Just to follow up on Binya's question, Mr. Chairman, you said that you could pullback the purchases possibly later this year. You sound a little bit less certain that it's going to happen later this year. So I'd like you--to ask you to talk a little bit more about your conviction about whether these are like--the pullback is likely to start this year, where you stand on that. And I also don't think I heard you mentioned that 7 percent unemployment number that you've talked--you talked about back in June. That was the rate that was--the unemployment rate that was supposed to prevail when the Fed was done doing this, is that no longer operative?

CHAIRMAN BERNANKE. So, there is no fixed calendar—a schedule, I really have to emphasize that. If the data confirm our basic outlook, if we gain more confidence in that outlook, and we believe that the three-part test that I mentioned is indeed coming to pass, then we could move later this year. We could begin later this year. But even if we do that, the subsequent steps will be dependent on continued progress in the economy. So we are tied to the data, we don't have a fixed calendar schedule, but we do have the same basic framework that I described in June.

The criterion for ending the asset purchases program is a substantial improvement in the outlook for the labor market. Last time, I gave a 7 percent as an indicative number to give you some sense of, you know, where that might be. But as my first answer suggested, the unemployment rate is not necessarily a great measure in all circumstances of the--of the state of the labor market overall. For example, just last month, the decline in unemployment rate came about more than entirely because declining participation, not because of increased jobs. So, what we will be looking at is the overall labor market situation, including the unemployment rate, but including other factors as well. But in particular, there is not any magic number that we are shooting for. We're looking for overall improvement in the labor market.

also:

ANNALYN KURTZ. Annalyn Kurtz with CNNMoney. This week marks five years since the financial crisis began, and Hank Paulson, who you worked very closely with, has said his biggest regret was that he wasn't able to convince the American people that what was done-- the bank bailouts--weren't from Wall Street, they were from Main Street. What is your biggest regret as you reflect on the five-year anniversary? And do you believe that the Fed, Congress, and the President have put the necessary measures in place to prevent another deep financial crisis?

CHAIRMAN BERNANKE. Well, on regrets, as Frank Sinatra says, I have many. I think my--you know, reasonably, the biggest regret I have is that we didn't forestall the crisis. I think once the crisis got going, it was extremely hard to prevent. You know, I think we did what we could, given the powers that we had, and I would agree with Hank that we were motivated entirely by the interest of the broader public, that our goal was to stabilize the financial system so that it would not bring the economy down, so that it would not create massive unemployment and economic hardship that was even more--that would be--would have been even more severe by many times than what we actually saw. So, I agree with him on that, and I guess, since you gave me the opportunity, I would mention that, of course, all the money that was used in those operations has been paid back with interest. And so, it hasn't been costly even from a fiscal point of view. Now, in terms of progress, that's a good question. I think we made a lot of progress. We had, of course, the Dodd-Frank law passed in 2010, and then we recently, you know, have come to agreement internationally on a number of measures, including Basel III and other agreements relating to the shadow banking system and other aspects of the financial system. I think that our-today, our large financial firms, for example, are better capitalized by far than they were certainly during the crisis and even before the crisis. Supervision is tougher. We do stress testing to make sure that firms can withstand not only normal shocks but very, very large shocks, similar to those they experienced in 2008. And very importantly, of course, we now have a tool that we didn't have in 2008--which would have made, I think, a significant difference if we had had it-which is the Orderly Liquidation Authority that the Dodd-Frank bill gave to the FDIC in collaboration with the Fed. Under the Orderly Liquidation Authority, the FDIC, with other agencies, has the ability to wind down a failing financial firm in a way that minimizes the direct impact on the financial markets and on the economy. Now, I should say, I don't want to overstate the case, I think there's a lot more work to be done. In the case of resolution regimes, for example, the United States has set the course internationally. Other countries and international bodies like the FSB are setting up standards for resolution regimes, which are very similar to those of the United States, which is going to make for better cooperation across borders. But we're still some distance from being fully geared up to work with foreign counterparts to successfully wind down international--multinational financial firm. And that's--we've made progress in that direction, but we need to do more, I think. So, I think there's more to be done. There's more to be done on derivatives, although a lot has been done to make them more transparent and to make the trading of derivative safer. But it's going to be probably some time before, you know, all of this stuff that has been undertaken, all of these measures are fully implemented. And we can assess, you know, the ultimate impact on the financial system.

also:

STEVE BECKNER. Steve Beckner of MNI. Mr. Chairman, a number of economists, and indeed, some of your Fed colleagues, have argued that the effectiveness of quantitative easing has greatly diminished, if not disappeared, and they point to the recent performance of the economy as proof of that. And there have been a number of people who have argued that there are regulatory and other impediments to growth beyond the reach of monetary policy. To what extent are these valid arguments? And if the economy does not speed up, that does not reach your objectives, how will you ever get out of quantitative easing?

CHAIRMAN BERNANKE. Well, on the effectiveness of our asset purchases, it's difficult to get a precise measure. There's a large academic literature on this subject, and they have a range of results, some suggesting that this is a quite powerful tool, some that it’s less powerful. My own assessment is that it has been effective. If you look at the recovery, you see that some of the strongest sectors, the leading sectors like housing and autos, have an interest sensitive sectors. And that these policies have been successful in strengthening financial conditions, lowering interest rates, and thereby promoting recovery. So I do think that they have been effective. You mentioned that there hasn't been any progress. There has been a lot of progress, as I said at the beginning. Labor market indicators, while still not where we'd like them to be, are much better today than they were when we began this latest program a year ago. And importantly, as actually is referenced in our FOMC statement, that happened notwithstanding a set of fiscal policies which the CBO said would cost between one and one and a half percentage points of real growth and hundreds of thousands of jobs. So, the fact that we have maintained improvements in the labor market that are as good or better than the previous year, notwithstanding this fiscal drag, is some indication that there is at least a partial offset from monetary policy. Now, just as you say, there are a lot of things in the economy that monetary policy can’t address. They include the effectiveness of regulation, they include fiscal policy, they include developments in the private sector. We do what we can do and what--if we can get help, we're delighted to have help from other policymakers and from the private sector and we hope that that will happen. The criterion for ending asset purchases is not, you know, some very high rate of growth. What it is, is the criterion--let me just remind you, the criterion is a substantial improvement in the outlook for the labor market and we have made significant improvement. Ultimately, we will reach that level of substantial improvement and at that point, we will be able to wind down the asset purchases. Again, you know, and I think people don't fully appreciate that we have two tools: We have asset purchases and we have rate policy and guidance about rates.

It's our view that the latter, the rate policy, is actually the stronger, more reliable tool. And when we get to the point where we can, you know, where we are close enough to full employment, that rate policy will be sufficient, I think that we will still be able to provide--even if asset purchases have reduced--we will still be able to provide a highly accommodative monetary background that will allow the economy to continue to grow and move towards full employment.

also:

PETER COOK. Peter Cook at Bloomberg Television. Mr. Chairman, one of my colleagues was remarking as we came in here, we don't often get surprises from the Federal Reserve. This was a surprise, you talked about--you hadn't telegraphed anything specifically, but you've seen the market reaction, I'm sure. My question for you is, were you intending a surprise today, and did you get the intended result judging from the market reaction? And related to that, by taking this action today, continuing the bond purchases going forward. At what point do you believe you're starting to complicate the exit strategy? Simply by continuing to keep the Fed's foot on the gas pedal, do you make life more complicated for the Federal Reserve down the road?

CHAIRMAN BERNANKE. Well, it's our intention to try to set policy as appropriate for the economy, as I said earlier. We are somewhat concerned. I won’t overstate it, but we do want to see the effects of higher interest rates on the economy, particularly in mortgage rates on housing. So to the extent that our policy makes conditions--our policy decision today makes conditions just a little bit easier, that's desirable. We want to make sure that the economy has adequate support and in particular, is less surprising the market or easing policy as it is avoiding a tightening until we can be comfortable that the economy is in fact growing, you know, the way we want it to be growing. So, this was a step--it was a step, a precautionary step if you will. It was a--the intention is to wait a bit longer and to try to get confirming evidence whether to these-to whether or not the economy is, in fact, conforming to this general outlook that we have. I don't think that we are complicating anything for future FOMCs. It's true that the assets that we've been buying add to the size of our balance sheet. But we have developed a variety of tools, and we think we have numerous tools that we--can be used to both manage interest rates and to ultimately unwind the balance sheet when the time comes. So I, you know, I'm--I feel quite comfortable that we can, in particular, that we can raise interest rates at the appropriate time, even if the balance sheet remains large for an extended period. And that will be true of course for, you know, future FOMCs as well.

also:

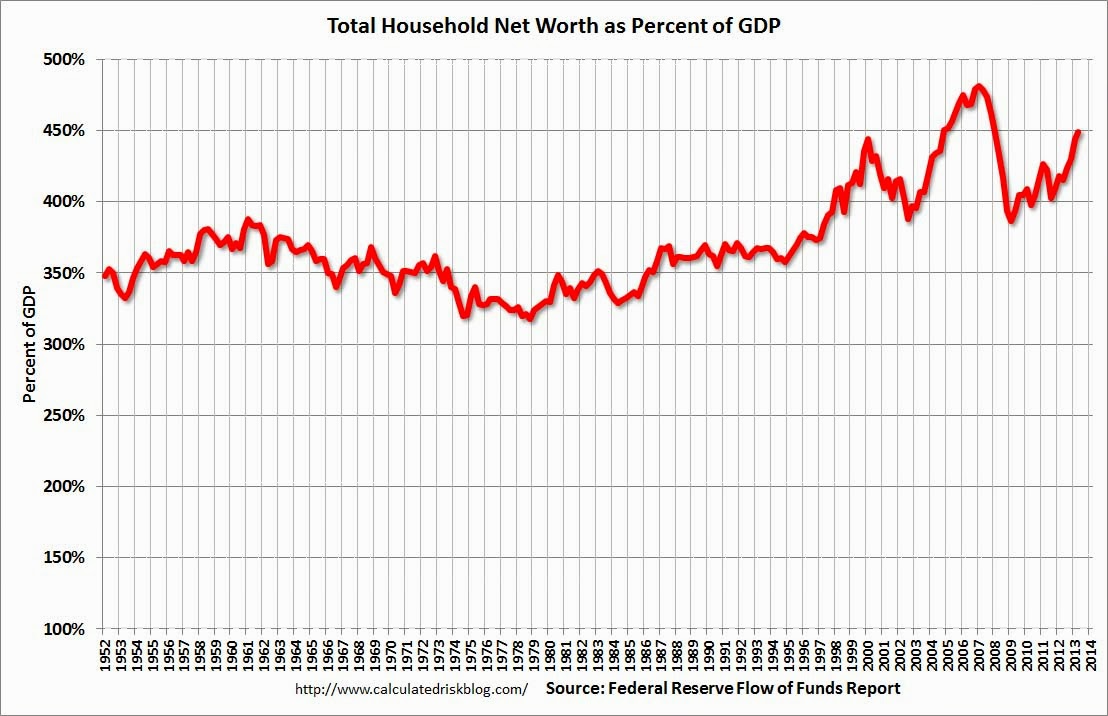

DON LEE. Don Lee, L.A. Times. As you may know, the Census Bureau reported yesterday that poverty rate and the median household income saw no improvement last year. And I wonder when you see median income is turning up significantly for most people, and in light of the fact that people in the middle and the bottom have seen very little of the gains relative to higher income households, how would you assess the--both quantitative easing and Fed policies?

CHAIRMAN BERNANKE. Sure. So that's certainly the case that there are too many people in poverty. There are a lot of complex issues involved. There are complex measurement issues, I would just have to mention that. There are a lot of issues that are really long-term issues as well. For example, it might seem a puzzle that U.S. economy gets richer and richer, and yet there are more poor people. And the explanation, of course, is that our economy is becoming more unequal. The more, very rich people and more people in the lower half who are not doing well, these are--there's a lot of reasons behind this trend, which have been going on for decades, and economists disagree about the relative importance of things like technology and international trade and unionization and other factors that have contributed to that. But I guess my first point is that these long run trends, it's important to address these trends but the Federal Reserve doesn't really have the tools to address these long run distributional trends. They can only be addressed really by Congress and by the Administration. And it's up to them, I think, to take those steps. The Federal Reserve is--we are doing our part to help the median family, the median American, because one of our principal goals, are--we have two principal goals, one is maximum employment, jobs; the best way to help families is to create employment opportunities. We're still not satisfied, obviously, with where the labor market, the job market is. We'll continue to try to provide support for that. And then the other goal is price stability, low inflation, which, of course, also helps make the economy work better for people in the middle and the lower parts of the distribution. So, we use the tools that we have. It would be better to have a mix of tools at work, not just monetary policy but fiscal policy and other policies as well. But the Federal Reserve, we can, you know, we only have a certain set of tools and those are the ones that we use. Again, our objective, our objectives of creating jobs and maintaining price stability, I think, are quite consistent with helping the average American, but there's limits to what we can do about long run trends and I think those are very important issues that Congress and the Administration, you know, need to look at and decide, you know, what needs to be done there.

_____

The Special Note summarizes my overall thoughts about our economic situation

SPX at 1714.23 as this post is written